Systemic and Segmental MSK Biomechanics – Online Course

From vector analysis to clinical decision-making in joint and spinal pathologies

This online course in musculoskeletal biomechanics teaches a physics-based clinical reasoning model for physiotherapists and rehabilitation professionals.

It connects vector analysis of muscular forces directly to therapeutic decision-making in joint and spinal pathologies — assessment, prediction, and treatment.

CPD certified (UK) and CEU approved (USA, Florida).

For Physiotherapists, osteopaths, and rehabilitation professionals.

Format 18 video modules — 32 hours on-demand · 6 hours downloadable PDF materials · Total learning time: 38 hours.

Instructors Mauro Lastrico, PT · Laura Manni, PT

Support Direct chat with instructors for clinical questions throughout the course.

Certifications 38 CPD hours (UK) · 45 contact hours / 4.5 CEU (Florida, USA)

Fee €610 · Secure payment via Stripe · 2 installments available

Who is this for

The course offers an interpretive and therapeutic model for chronic, recurrent, or treatment-resistant joint and spinal pathologies. A unified biomechanical framework from assessment to intervention.

The complexity is in the clinical reasoning. The manual technique is accessible — no prior experience with this method is required.

The scientific content of this course has been independently evaluated by two accreditation bodies:

The CPD Certification Service (UK) examined the biomechanical model, the teaching structure, and the coherence between stated objectives and actual content:

"An advanced online course providing rehabilitation professionals with a scientifically grounded model for assessing and treating musculoskeletal dysfunctions through systemic biomechanics. It integrates physics, myofascial chain analysis, and vector-based muscle assessment to identify primary and secondary shortenings, optimize joint alignment, and restore functional balance."

The course has also been evaluated and approved by CE Broker (USA, Florida) for 45 contact hours / 4.5 CEU, following independent review of course content and learning objectives.

The course is built around three clinical questions — the same ones you face with every patient:

- WHY a specific joint or spinal segment is mechanically altered

- WHEN the symptom is local, referred, or the expression of a systemic adaptation

- HOW to intervene at the segmental and systemic level — and in what sequence

Vector-based biomechanical analysis is the tool that connects assessment to these decisions. It allows you to move from observation to prediction, and from prediction to targeted intervention.

You identify the muscular vectors responsible for the alteration. You anticipate how the system will evolve. You verify whether your intervention is working.

The logic is the same from the simplest case to the most complex:

- observe the symptomatic area

- formulate a biomechanical hypothesis — segmental and systemic

- intervene and verify the result.

This course integrates two levels: an interpretive model — physical laws, reproducible criteria — and a clinical practice adapted to each patient's response. The model tells you how to read what you observe. The clinical practice tells you how to intervene.

The interpretive model is grounded in applied physics. Joint alterations are the result of force configurations generated by muscular shortenings, anatomical dominances, and structural asymmetries. It gives you a consistent framework: you understand what you observe, you identify the most probable directions of alteration, you build stable clinical reasoning.

Clinical practice requires continuous adaptation. You modify priorities, sequences, and strategies based on what the patient's body returns during assessment and treatment.

The model tells you where to look and what to expect. The practice tells you what to do with that specific patient at that specific moment. The model is transferable — it applies to everyone. The practice is individual — it changes every time.

| INTERPRETATIVE MODEL | CLINICAL PRACTICE |

|

|

Joint and spinal alterations originate from a consistent mechanical process: structural shortening of the connective component of muscle tissue.

Unlike the contractile component (which behaves elastically and returns to its original length), the connective matrix retains deformation over time. This generates permanent traction on bone insertions and progressively alters joint axes.

A structurally shortened muscle is simultaneously too strong statically — its Resistant Force (RF) maintains constant traction that displaces joint alignment — and too weak dynamically — its Working Force (WF) is reduced because energy is dissipated overcoming internal connective resistance.

This is why strengthening a shortened dominant muscle often worsens the clinical picture: you are adding power without releasing the brake.

The therapeutic response

Conventional approaches — mobilization, passive stretching, tone modulation — can influence the contractile component but do not reach the connective substrate responsible for structural shortening.

The course teaches the use of isometric contractions performed in maximum physiological elongation, guided by vector analysis. This approach acts directly on the shortened connective tissue, reducing RF and restoring available WF.

The technique is derived from the Mézières Method, selected for its mechanical coherence with the model. The interpretive framework — vector analysis, RF-WF mechanics, anatomical dominances — is universal and applies independently of the therapeutic tool. The technique adopted is Mézières, because in over four decades of clinical comparison it has demonstrated stable results when systemic rebalancing is achieved.

Intervention is always guided by biomechanical analysis: you know which muscles to target, in what sequence, and you verify the result in real time.

The full physical and clinical foundations are developed in the course modules and in the downloadable e-book.

Muscles are not distributed symmetrically around joints. Within every agonist–antagonist system, structural differences exist — in muscle number, cross-sectional area, and angle of force application. These differences create permanent directional dominances: they are anatomical facts, not dependent on the state of contraction.

When Resistant Force increases, these dominances manifest first. You already know in which direction that joint will alter.

The same logic applies between anatomically symmetrical muscles. Wherever bilateral muscles develop asymmetric RF — vertebral rotations are one example — the vector resultant determines the direction of alteration.

The principle applies to any joint. Vector analysis allows you to apply it case by case.

You start from dominances, predict the alterations, verify them during assessment, identify the causal vectors. You have a direction before you touch the patient.

The symptom is local. The forces generating it may not be.

Treatment always follows a dual logic: resolve the specific mechanical conflict generating the symptom, and verify that the local correction does not create compensations or joint misalignments elsewhere.

An intervention that improves the segment but creates problems in the system will not last. A purely systemic intervention that does not address the local mechanical conflict may improve the general perception without solving the problem.

At the end of each session, three conditions must be present simultaneously: local improvement, absence of new joint compensations, and greater system adaptability. If any one is missing, the result tends to be unstable.

The strategy is adaptive. Sometimes you start from the local conflict, sometimes from systemic work. It depends on the dominances present and the patient's response. The sequence is not fixed — it is guided by vector analysis and verified step by step.

The model is particularly effective where conventional segmental approaches reach their limits:

- Orthopedic joint and spinal pathologies

- Chronic musculoskeletal symptoms unresponsive to standard treatments

- Pain that alternates or migrates between body regions

- Recurrent issues without clear traumatic cause

- Persistent functional limitations post-surgery

With every patient you know why that joint is altered, what to treat first, in what sequence, and how to verify whether your decision is working.

This changes assessment, treatment, and the way you explain to patients what you are doing and why.

Realistic expectations

In primary muscular dysfunctions, measurable changes in joint alignment and symptom reduction typically appear within 2–10 sessions (weekly, 60 minutes), depending on severity and accuracy in identifying causal vectors.

Long-term stability depends on the depth of systemic rebalancing achieved. Continuing beyond symptomatic remission consolidates vector rebalancing and reduces recurrence.

As in all clinical practice, approximately 10–15% of patients may show limited response. This reflects biological variability and cases where the primary cause lies outside the domain of muscular biomechanics. Persistence of symptoms beyond 10 sessions requires systematic reassessment.

Enroll now

Download the complete program

Lesson 5 — Supine position work | Sagittal plane Duration: approximately 2 hours

A full lesson from the course, uncut. Representative of the teaching format, the level of depth, and the clinical reasoning used throughout the entire course.

[VIDEO EMBEDDED]

Original Italian lectures, fully dubbed in English by professional voice actors.

The course starts from the foundations of the biomechanical model and structured clinical assessment. It progresses through segmental analysis — spine, lower limbs, upper limbs, TMJ — to clinical reasoning on complex cases: when the symptom is local, when it is compensatory, where to intervene first.

- Theoretical Foundations and Assessment (videos 1–4 – 8h 30min)

Causes of muscular shortening, Resistant Force and Working Force, vector analysis applied to the muscular system, three-dimensional patient assessment, manual techniques. Theory and practical demonstrations.

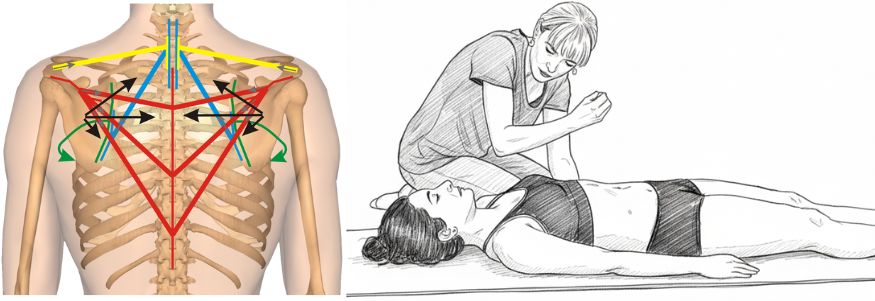

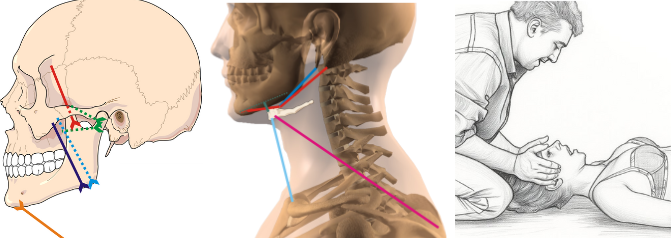

The core innovation: transforming anatomical muscles into force vectors to predict their mechanical effects. Left: Vector analysis reveals how shortened muscles create predictable force patterns affecting scapular positioning. Right: Clinical application where the therapist uses this vector understanding to guide treatment, working with therapeutic breathing to reduce resistant forces.

- Sagittal Plane Corrections (videos 5–6 – 3h 55min)

Evaluation and corrective treatment, both segmental and systemic, of the cranio-vertebro-sacral system in the sagittal plane. Theory and practical demonstrations.

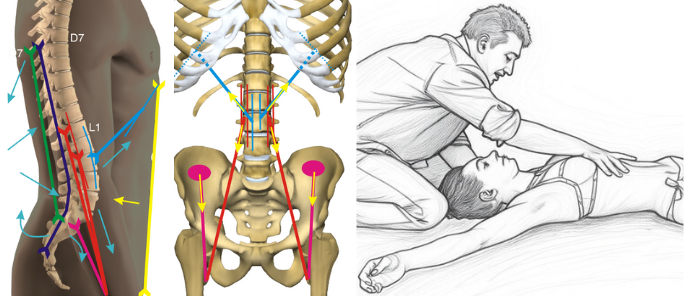

Vector analysis of forces acting between D7 and sacrum with their resultant force lines. Clinical application exemplifies how vector understanding guides therapeutic positioning - one example from the comprehensive toolkit of sagittal techniques presented in the course.

- Frontal and Rotational Plane Corrections (videos 7–9 – 5h 51min)

Evaluation and corrective treatment, both segmental and systemic, of the cranio-vertebro-sacral system in the frontal plane; evaluation and treatment of upper limb pathologies and their connection with vertebral, costal, and hyoid dysfunctions. Theory and practical demonstrations.

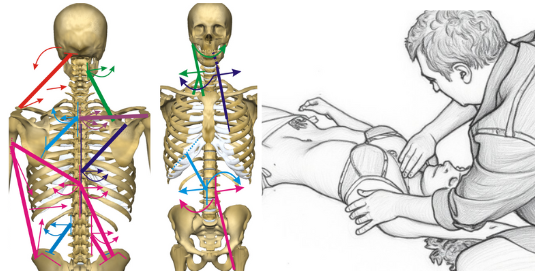

Vector analysis in the frontal plane reveals asymmetries and rotational patterns of the cranio-vertebro-pelvic system. Mechanical connections between upper limb and vertebro-costal complex guide integrated treatment - one of the specific approaches for frontal and rotational dysfunctions.

- Lower Limbs and Specific Techniques (videos 10–12 – 5h 36min)

Evaluation and treatment, analytical and systemic, of lower limb pathologies and their relationship with vertebral dysfunctions. Theory and practical demonstrations.

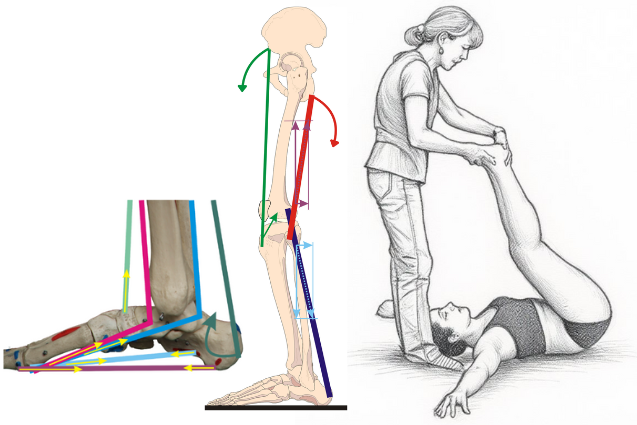

Vector representation of force lines acting on medial plantar arch and lower limb, with example of their treatment. These mechanical relationships enable both local and systemic therapeutic interventions.

- Specific Districts (videos 13–15 – 5h)

Distinction between primary muscular problems and those secondary to structural alterations from other systems. Evaluation and treatment of TMJ disorders and the multidisciplinary approach, dynamic analysis and identification/treatment of altered patterns, treatment of humeral and sternoclavicular subluxations. Theory and practical demonstrations.

Vector analysis of temporomandibular joint, hyoid bone and cervical connections, with specific clinical application. Understanding these anatomical relationships determines whether direct treatment or multidisciplinary referral is indicated.

- Clinical Reasoning (videos 16–18 – 3h 04min)

The symptom as an expression of a local or referred problem; from static and dynamic objective examination to treatment planning. Scoliosis: evaluation and treatment. Theory and practical demonstrations.

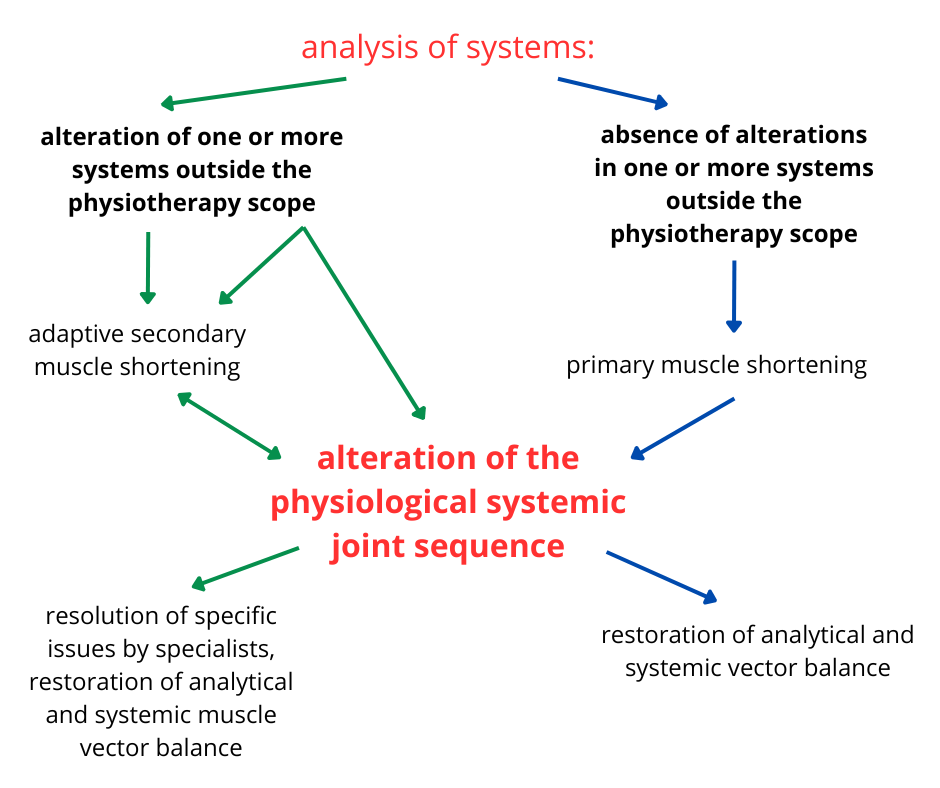

Systemic clinical reasoning: from systems analysis to treatment planning. The diagram illustrates the decision-making process for distinguishing between primary muscle shortenings (directly treatable) and secondary ones (requiring multidisciplinary approach), guiding optimal therapeutic strategy.

📌 Each video includes theoretical lessons, live demonstrations, and downloadable PDF materials. Download full program

Mauro Lastrico, PT · Laura Manni, PT Trained directly with Françoise Mézières (Paris, 1988–1990)

Over 40 years of clinical experience in musculoskeletal rehabilitation. Over the past three decades they have systematized the clinical foundations learned from Mézières into the physics-based biomechanical model taught in this course, integrating vector analysis, connective tissue mechanics, and joint axis sequencing.

More than 6,000 physiotherapists trained through AIFIMM, the postgraduate institute they founded in 1996. Accredited in Italy (ECM — Ministry of Health), UK (CPD), and USA (CEU, Florida).

Teaching quality — official data

ECM is the mandatory continuing education system for healthcare professionals in Italy, managed by the Ministry of Health. Course evaluations are collected independently.

From 6,147 evaluations (1997–2024):

- 78% rated the training very useful

- 71% rated overall quality excellent

- 77% rated practical content delivery excellent

- Over 90% would recommend the course to a colleague

Books

Musculoskeletal Biomechanics and the Mézières Method First edition 2016 — third printing 2023 Mauro Lastrico · Demi Edizioni

Systemic and Segmental Musculoskeletal Biomechanics — Principles of Applied Physics for Clinical Practice Mauro Lastrico · Laura Manni · Forthcoming 2026

Articles

The following articles have been independently evaluated and published by the CPD Certification Service (UK):

Muscle Shortening and Joint Dysfunction – Physical and Clinical Mechanisms

Body Equilibrium – A Physical-Clinical Interpretation of Human Upright Stability

Vector Analysis in Musculoskeletal Biomechanics - Part 1: Foundations and Clinical Principles

Vector Analysis of the Vertebral Column in the Frontal Plane – Part 1

Vector Analysis of the Vertebral Column in the Frontal Plane – Part 2

The Mézières technique has received scientific validation through RCTs conducted in European university centers and published in peer-reviewed databases (VAS, Roland-Morris, Berg Balance Scale; intervention duration 5–24 weeks; statistically significant efficacy superior to standard treatments, p<0.001).

Why large-scale research is limited

Each treatment requires individual biomechanical assessment, continuous strategy adaptation, extended individual sessions (60 minutes), and therapists with advanced specific training. This individualization is the core of clinical efficacy, but makes standardization for large-scale RCTs impossible.

The AIFIMM approach

The model is founded on two complementary pillars:

Mechanistic reasoning — vector mechanics, connective tissue behavior, demonstrable relationships between shortening, RF-WF, and articular conflicts.

Evidence-informed practice — verifiable clinical observation, measurable outcomes over time, coherence between acting forces and observed axial changes.

The absence of large RCTs does not derive from methodological weakness, but from the impossibility of standardizing what is, by nature, individualized.

The biomechanical model presented in this course is not "the truth about the human body."

It is the most rigorous hypothesis we have been able to build over 40 years of clinical and theoretical work, grounded in current knowledge of physics, physiology, and biomechanics, and in the clinical observations that Françoise Mézières transmitted to us.

We know that today's knowledge will be refined and surpassed. Mézières collected the clinical observations of her time and translated them into groundbreaking insights. We translated those insights into verifiable physical and mathematical language. Others, after us, will refine, correct, and improve.

If current knowledge were complete, we would all be doing the same thing. The existence of different approaches does not mean some are right and others wrong — it means we are still exploring a complex system with limited tools.

We do not present ourselves as holders of absolute certainties. We encourage participants to test what we teach against their own clinical practice, to compare it with other frameworks, and to question what does not hold up.

Scientific rigor means building testable hypotheses, refining them, and accepting they will be surpassed.

- 18 video modules (32 hours) — demonstrations with detailed biomechanical analysis on real patients

- Complete PDF materials — the full content of Systemic and Segmental Musculoskeletal Biomechanics — Principles of Applied Physics for Clinical Practice (Lastrico, Manni — forthcoming 2026), organized by topic with clinical illustrations. Over 25 downloadable resources covering the theoretical foundation of the model taught in the course.

- On-demand access: available 24/7 for 12 months

- Dedicated chat with Mauro Lastrico and Laura Manni for clinical questions throughout the course

Video demonstrations include precise anatomical landmarks for positioning, patient response indicators, verification criteria, and common errors. Palpatory assessment and positioning require direct practice, but the course provides the visual and conceptual tools to self-correct through objective patient responses: changes in joint alignment, muscle tension, and patient feedback.

Final test: 20 multiple-choice questions. Upon passing: digital certificate delivered by email.

Fee

€610 · or 2 installments of €305 · Secure payment via Stripe · No hidden fees, no renewals.

Immediate access after payment.

Certifications included:

- 38 CPD hours (UK) — The CPD Certification Service, Provider No. 21418

- 45 contact hours / 4.5 CEU (USA, Florida) — CE Broker, Provider ID 50-54885

CE Broker Tracking 20-1318645 · FPTA Approval CE25-1318645 · Effective 01/01/2026–12/31/2026. "Accreditation of this course does not necessarily imply the FPTA supports the views of the presenter or the sponsors."

Enroll now

Download the complete program

The sections below develop the physical foundations and clinical applications of the model in detail: connective tissue mechanics, RF-WF model, vector analysis, complex systems, pain and clinical reasoning, therapeutic strategies.

Further resources:

📘 E-book — Physical and clinical foundations of the biomechanical model

📄 Systemic and Segmental Musculoskeletal Biomechanics — article collection with downloadable PDFs

Why muscles shorten and what happens to joint biomechanics

A consistent phenomenon is observed in clinical practice: even in the absence of specific pathologies, muscles tend to progressively shorten over time, altering both static alignment and joint dynamics.

The model explains this phenomenon through the physical laws of material deformation.

From a biomechanical perspective, muscle is not a homogeneous structure: the contractile component behaves as a reversible elastic material, while the connective component exhibits plastic behavior, retaining residual deformation proportional to the product of force × time.

This is not pathology — it is physics applied to biological tissues.

Since muscle always acts as a compressive force and the skeleton passively adapts to force resultants, muscular shortenings become the primary determinant of joint axis alterations.

On these foundations rests the RF–WF model, the core of the biomechanical interpretation:

A shortened muscle is simultaneously "too strong" from a static perspective (high Resistant Force, altering joint alignment) and inefficient from a dynamic perspective (reduced Working Force and increased compensations).

Resistant Force and Working Force are inversely proportional: as one increases, the other decreases.

This paradox explains why muscle strengthening, in the presence of structural shortenings, often fails to resolve the problem — and can worsen it.

Only by reducing Resistant Force can mechanical efficiency and function be restored.

When you palpate a shortened muscle, you are not just feeling "tension" — you are perceiving the coexistence of two problems: tissue that blocks the joint (high RF) and that simultaneously cannot do its job (low WF).

It is like driving with the handbrake engaged: the harder you press the accelerator, the more force you need to move, but that force does not move the car — it fights the brake.

This is why asking a patient to "strengthen" that area often worsens pain: you are adding power to the engine without releasing the brake.

Why joint alterations follow specific and predictable directions

Once it is clear why muscles shorten, the next question is: why do joint alterations follow recurrent and predictable directions?

This is made possible by vector analysis of muscular forces.

Muscles are not distributed symmetrically around joints.

Within every agonist–antagonist system, intrinsic anatomical asymmetries exist — in muscle number, force line length, and angle of application — creating genuine vector dominances, independent of training or voluntary control.

When Resistant Force increases, these dominances manifest first and drive the loss of physiological joint sequencing.

These are not "random compensations" — they are the predictable outcome of physical laws applied to anatomy.

This is why certain alterations are clinically recurrent. Some examples:

- In the glenohumeral joint, the humerus tends toward internal rotation and anterior displacement

- The scapulae tend toward adduction with reduction of physiological thoracic kyphosis

- The foot tends toward supination and cavus, often compensated proximally

In clinical practice, when you observe these patterns on the patient's body, the humerus is already internally rotated before you ask for any movement. It does not "internally rotate" — it is already there.

Like a crack in a wall that follows lines of least structural resistance. The anatomical dominance is already active in static posture, and movement merely amplifies it. This is why assessment begins with observation: it already tells you where to look.

Clinical reasoning changes fundamentally: you start from knowledge of anatomical dominances, predict the alterations, verify them during assessment, and rapidly identify the responsible muscular vectors.

This predictive capacity is confirmed in neurological conditions as well: when central inhibitory control is lost, as in spastic hemiparesis, the same anatomical dominances emerge in amplified form. Different mechanisms, same structural reality.

The connection with the RF–WF model is direct: when Resistant Force increases, subdominant vectors can no longer compensate, and the joint deviates along anatomically dominant directions.

In this model, muscle shortening is the final outcome of tone regulation processes involving multiple systems.

Regardless of the initial trigger, muscle is the final effector — the structure through which the body realizes adaptation. The model distinguishes different levels of origin.

Neurophysiological level: basal tone is regulated by sensory–motor integration circuits.

The nervous system uses muscle tone as a protective strategy, through pain reflexes that may activate after pain onset (reactive response) or in anticipation of it (preventive response).

When these contractions are maintained over time, they involve the connective component and transform into structural shortenings. This level lies fully within the scope of physiotherapy, because it manifests in the musculoskeletal system.

Biomechanical level: increased tone represents an adaptive response to altered loads, joint axes, or centers of gravity.

The system preserves equilibrium at the cost of a self-reinforcing cycle: mechanical alteration → increased tone → shortening → further alteration.

The result is increased Resistant Force, reduced Working Force, loss of efficiency, and progressive rigidity. This level also belongs to physiotherapy, because it produces observable and treatable joint alterations.

There is also a psychosomatic level, documented in the literature, in which prolonged emotional states modulate muscle tone through neurovegetative and central pathways, potentially leading to structured orthopedic presentations.

Whatever the level of origin, the common denominator remains the same: muscle is the final effector.

Very different clinical histories may therefore converge toward similar shortenings and compensatory patterns.

In practice, the shortened muscle is often the "final stop" of very different pathways.

One patient with chronic low back pain may present structural shortenings originating from altered mechanical loading; another from protective pain strategies maintained for years after trauma; another from distant compensations — an unresolved foot problem that modified weight-bearing patterns.

The final pattern — accentuated lordosis, anterior pelvic tilt, shortened psoas — may appear identical.

This is why assessment does not stop at reading "what you see," but seeks to understand which level is actively maintaining the problem, to avoid treating only the final effect.

The task of the model is not to explain every possible cause, but to interpret what is biomechanically relevant: distinguishing between primary cause, muscular adaptation, and articular consequences.

Why systemic analysis is a clinical necessity

In 1947, Françoise Mézières formulated what she called her capital observation: the numerous muscles behave as a single muscle, too strong and too short.

Today this insight finds explanation in complex systems theory: systems in which many elements interact interdependently.

The human musculoskeletal system is, in every sense, a complex system. This means that no region functions in isolation and that any local intervention inevitably produces adaptations at a systemic level.

The concept of muscle chains represented an initial step beyond segmental thinking. This model takes it further, placing it within a biomechanical framework grounded in physical laws and force analysis.

In a complex system, the symptom does not necessarily coincide with the site of the problem.

Local pain may be the expression of an altered systemic organization, and attempts at isolated correction can be not only ineffective, but mechanically counterproductive.

This is why instructions like "stand up straight" or many voluntary self-corrections are often ineffective: they increase overall tone and Resistant Force, worsening the system's energy balance.

Another characteristic of complex systems is the presence of emergent abilities.

When specific muscles become ineffective due to excessive shortening, the system does not stop: it bypasses them, activates alternative synergies, and develops substitution patterns.

This is clearly visible during movement: you ask the patient to raise the arm and the first thing that elevates is the shoulder, or you see the pelvis shift when only the femur should flex.

This is not "incorrect" — it is the only strategy the system has found to complete the requested movement when the muscles that should perform it are too shortened to work.

It is like taking a winding alternative road when the direct route is blocked: it works, but it costs far more in energy and wear.

This explains why isolated strengthening of subdominant muscles does not resolve the problem, and why certain monoarticular muscles are systematically excluded from movement.

In this model, a system functions efficiently when it operates at the edge of chaos — that zone of maximum flexibility and adaptability where the body is ready to respond to any stimulus without rigidity — a condition in which Working Force prevails over Resistant Force.

When Resistant Force increases, the system becomes rigid, energy expenditure rises, and physiological joint sequencing is lost.

An efficient system moves fluidly, with no visible effort, with smooth transitions between segments. When RF increases, movement becomes fragmented, "jerky," with visible pauses and compensations.

The patient tells you "I struggle with simple things" — not because of weakness, but because every gesture requires three times the energy.

It is like pushing a shopping cart with the wheels locked: you push hard but barely move, and you tire immediately.

From symptom to the distinction between local dysfunction and systemic organization

In musculoskeletal pain, the symptom always represents real clinical information, but it does not automatically coincide with the cause of the problem. In some cases the pain is genuinely local; in others, the symptomatic joint represents the outcome of an adaptive organization involving multiple regions.

Clinical reasoning is founded on the need to distinguish between local and referred pain.

The muscle tone observed in clinical practice is the result of neurophysiological and biomechanical regulation processes aimed at maintaining stability and continuity of movement.

When these adaptive strategies persist over time, they may involve the connective component of muscle, transform into structural shortenings, and alter physiological joint sequencing.

Pain often emerges when the system's adaptive margins are reduced.

In the model, clinical reasoning integrates:

- observation of static and dynamic patterns

- analysis of vector dominances

- differentiation tests aimed at determining whether the symptomatic region is the primary cause or the site of expression of a broader adaptive organization

When pain originates locally, intervention on the symptomatic region can be resolutive.

When pain is referred, treating exclusively the site of the symptom produces transient improvements that will not persist over time.

In practice, it is like a warning light on a car dashboard: it could be a faulty sensor (local problem — replace the sensor and you are done) or an overheating engine (systemic problem — the light is just the message).

In the first case, you treat where it hurts and the patient improves stably.

In the second, the shoulder pain you treat may calm down for a few days, but if the problem originates from a blocked pelvis forcing the spine to compensate, the shoulder will hurt again until you address the primary restriction.

This is why differentiation tests are fundamental: not to "prove" that pain is referred, but to avoid chasing the symptom without modifying the forces that regenerate it.

A key step in clinical reasoning is the distinction between primary and secondary muscle shortenings.

In primary shortenings, the muscular system is the origin of joint misalignment, and vector rebalancing can be stable and effective. In secondary shortenings, the muscle represents an adaptation to dysfunction originating from other systems, requiring multidisciplinary assessment to avoid recurrence.

This is why some improvements last and others do not. Not because treatment "works or doesn't work," but because the forces responsible for the misalignment have, or have not, been correctly identified and modified.

The following simplified case illustrates how clinical reasoning is applied within the model. Real clinical situations are often more complex and require multiplanar assessment and continuous adaptation, but the decision-making logic remains the same.

Clinical case A patient presents with anterior shoulder pain and limited abduction. No recent trauma.

Phase 1 — Prediction through vector analysis Based on anatomical dominances, vector analysis predicts internal rotator dominance. When Resistant Force increases in these muscles, the humeral head tends to shift anteriorly, reducing the subacromial space.

Phase 2 — Verification during assessment Physical examination confirms the predicted pattern:

- anteriorized humeral head

- static internal rotation of the humerus

- scapular adduction

Phase 3 — Decision sequence Intervention priorities are defined by force analysis, not by predefined protocols:

- address the subscapularis first (dominant vector in anteriorization)

- verify scapular repositioning, as adductors may maintain residual tension

- assess cervical compensations, frequently associated with scapular rigidity

Each step is guided by mechanical reasoning and continuously adjusted according to observed responses.

Phase 4 — Immediate verification At the end of the session:

- has the humeral head repositioned?

- has abduction improved?

- is the system more elastic, or have new rigidities emerged?

If yes, the causal vector has likely been correctly identified. If not, reassessment is required: are there unrecognized compensations? Is the shortening primary or secondary?

This is the clinical reasoning taught in the course: not "what to do for the shoulder," but how to analyze the forces altering the shoulder and adapt intervention based on system response.

In real clinical practice, every patient requires individual assessment, consideration of systemic compensations, and strategies that evolve continuously in response to mechanical feedback.

How the model guides clinical intervention

The objective of treatment is to modify the forces maintaining the system in a mechanically inefficient state, reducing Resistant Force (RF) and restoring genuinely available Working Force (WF).

This requires a fundamental distinction: the two components of muscle tissue — contractile and connective — respond to different stimuli and cannot be treated with the same approach.

Spontaneous movement, though essential for function, is insufficient to re-lengthen a structurally shortened muscular system: it always respects the limits already in place and the boundaries the nervous system has accepted as safe.

It is like trying to touch your toes: you reach as far as your body "allows" you to go, even if you push. That limit is not structural — it is the point where the nervous system says "stop, further is dangerous." Spontaneous movement always respects this safety boundary. The shortened connective tissue lies beyond that boundary: reaching it requires guided work, where the therapist progressively brings the patient beyond the habitual limit, under controlled and safe conditions.

When shortening involves the connective component, length recovery requires guided therapeutic intervention capable of bringing tissue beyond the limits of spontaneous adaptation.

Acting only on muscle tone, mobilizing or passively stretching, may be effective on the contractile component but remains insufficient on the connective substrate responsible for residual shortening.

This is why the model employs isometric contractions performed in maximum physiological or relative elongation, within a strategy continuously adapted to system response.

The technique is never applied automatically. The same maneuver can produce opposite effects depending on the mechanical context: if performed below the correct threshold, it can further increase Resistant Force. This is why precision of positioning, reading of dominances, and continuous observation of patient response are clinically decisive.

Treatment always follows a dual logic: resolve the specific mechanical conflict generating the symptom, and verify that the local correction does not generate compensations or joint misalignments elsewhere.

An intervention that improves the local area but rigidifies the system is destined to fail. A purely "global" approach that does not address the real conflict may improve the general sensation without solving the problem.

In practice, you see patients who leave the session feeling "looser," breathing better, feeling freer — but if you ask them to repeat the movement that caused pain, the conflict is still there. It is like loosening every bolt on a machine except the one that is stuck: everything feels softer, but the part does not move. You need to find where the tension truly concentrates — the shoulder that does not abduct, the pelvis that does not rotate, the knee that does not extend — and work there with precision, without rigidifying everything else.

Every observable configuration, even when it appears pathological, represents the best adaptive solution the system has found at that moment. Improvement is not defined by visual symmetrization, but by the reduction of overall tension, increased systemic space, and recovery of functional efficiency.

Treatment effectiveness criteria are not limited to immediate symptom relief. At the end of a session, three conditions must be simultaneously present: local improvement, absence of new compensatory strategies, and greater system adaptability. If even one is missing, the result tends to be unstable.

When you verify at the end of a session, you do not just ask "has the pain gone?" but also "how does the patient move now?" and "where has the tension gone?"

If the shoulder has unblocked but the patient is now holding the neck rigid, you have moved the problem. If the patient feels better but movement is still fragmented, you have reduced the symptom but not the inefficiency.

When all three criteria are present together — reduced pain, fluid movement, more elastic system — the improvement is far more likely to persist. When even one is missing, the result risks being transient.

This is why the model does not propose standardized sequences but an adaptive clinical strategy. Intervention priority varies according to the dominances present and system response: sometimes it is necessary to work on systemic aspects first, sometimes to address the segmental conflict directly, always avoiding overall rigidity.

In clinical application, this approach proves particularly effective in chronic, recurrent, or resistant cases — when symptoms reappear despite previous treatments, often because the forces regenerating them have not been identified and modified.

Treatment is always individual, active, and guided. It requires time, listening, and observation, because the clinician's task is not only to intervene, but to understand and explain.

Vector analysis thus becomes both a clinical and a communicative tool: it allows the construction of verifiable reasoning and makes the patient an active participant in the therapeutic process. This shared understanding is one of the main factors explaining the stability of results over time.

What is vector analysis in musculoskeletal biomechanics? Vector analysis represents each muscle as a line of force defined by magnitude, direction, and point of application. When multiple muscles act on the same joint, their forces combine into a resultant that determines joint positioning. This course teaches how to use vector analysis to predict joint alterations, identify causal muscles, and guide treatment decisions.

What is the difference between Resistant Force and Working Force? A structurally shortened muscle generates two simultaneous forces: Resistant Force (RF) — permanent traction on bone insertions that alters joint alignment — and Working Force (WF) — the muscle's actual capacity to produce useful movement. RF and WF are inversely proportional: as one increases, the other decreases. This relationship explains why strengthening a shortened muscle often worsens symptoms.

How does this approach differ from standard biomechanics courses? Most biomechanics courses focus on assessment and analysis. This course connects vector-based assessment directly to therapeutic decision-making: which muscles to treat, in what sequence, and how to verify the result. The model is predictive — anatomical dominances allow you to anticipate joint alterations before examining the patient.

What is the Mézières technique and why is it used in this course? The Mézières technique uses isometric contractions performed in maximum physiological elongation to reduce structural shortening of the connective component of muscle tissue. It was selected for this course because of its mechanical coherence with the vector-based biomechanical model. The interpretive framework is universal; the technique adopted is Mézières.

Can this model be integrated with other therapeutic approaches? Yes. The interpretive framework — vector analysis, RF-WF mechanics, anatomical dominances — is independent of the therapeutic tool used. It provides clinical reasoning criteria that can inform any manual or exercise-based approach, provided mechanical coherence is respected.

What conditions can be treated with this approach? The model applies to orthopedic joint and spinal pathologies, chronic musculoskeletal symptoms unresponsive to standard treatments, pain that migrates between body regions, recurrent issues without clear traumatic cause, and persistent functional limitations post-surgery.

Is the course delivered in English? Yes. All video lectures are original Italian recordings fully dubbed in English by professional voice actors. All written materials and resources are in English. You can verify the audio quality by watching the free 2-hour sample lesson.

Are CPD/CEU credits recognized in my country? UK: 38 CPD hours, fully recognized. USA (Florida): 45 contact hours / 4.5 CEU, officially approved. EU, Australia, New Zealand: CPD is widely recognized. Canada: often recognized — check with your provincial regulatory body.

Do I need advanced physics or mathematics? No. Biomechanical principles are introduced progressively through clinical examples. If you understand basic anatomy and physiology, you have the foundation needed.

How much time do I need per week? The course is entirely self-paced with 24/7 access for 12 months. Most participants complete it in 3–6 months, dedicating 2–4 hours per week.

Is there instructor support? Yes. Dedicated chat with Mauro Lastrico and Laura Manni for clinical questions, case discussions, and clarifications throughout the 12-month access period. Response time typically within 24–48 hours.

Can I download the videos? Videos are streamed on-demand (not downloadable) and available 24/7 for 12 months. All PDF materials are downloadable.